Don't panic! Designing against dread

What is critical design and can it provide the lead for better sensemaking? We explore how critical design as cultural cartography makes visible the social relations that commercial design naturalizes, creating entry points into complex discussions about values, power, and futures.

"We live in a contradiction, a brutal state of affairs, profoundly inegalitarian – where all existence is evaluated in terms of money alone – is presented to us as ideal. To justify their conservatism, the partisans of the established order cannot really call it ideal or wonderful. So instead, they have decided to say that all the rest is horrible."

— Alain Badiou

In the later years of my professional life, I have been feeling the need to understand if there is an aspect of what I do with my designer identity (being a designer pretty much my whole career) that can contribute meaningfully to the world. Not how they have taught us in earlier stages of our career, that "design will change the world", but more like, what can I do with the skills that I have, to become a net-positive contributor to the planet, rather than chasing profits, maximizing shareholder value, or submitting to the god of business-as-usual, growth.

So in this essay, I want to talk about critical design, because it is something that I have been trying to use by creating modes of inquiry towards topics that affect my profession and thus my career: companies, AI slop, and duh... capitalism. It is one of the few skills that I feel is not favorable in the current business setting, but it is a fundamental skill of sensemaking.

But before we start talking about critical design, we first have to take a look at the emergence of the term and previous work that has tried to define it. Critical design is often also referred to as discursive design, and it operates as a mode of inquiry that interrogates the assumptions embedded in designed objects and systems. Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby articulated this practice in their book "Design Noir" (2001) and developed it further in "Speculative Everything" (2013), describing it as design that asks questions rather than solves problems. It provokes debate rather than attempts to settle it. Critical design operates as a form of cultural cartography, mapping the terrain of our current regime, while sketching the new paths where alternative futures might become possible.

Where commercial design naturalizes existing social relations of business-as-usual and economic logics of growth, critical design makes these relations visible and contestable. It creates propositions that function as entry points into complex discussions about values, power, and possible futures. Of course, the attributes 'discursive', 'speculative', or 'inquiry' that often coexist with the term 'critical' design do not necessarily mean that the practice has to stay in the abstract. It doesn't have to be just a conversation. Critical design can become a powerful prototyping mechanism (or even a company). Something that contains an alternative paradigm than what already exists, thus challenging the existing conditions in the world.

This capacity to make visible what has been naturalized is an urgent practice for sensemaking when we consider the scale of the complexity of what we're trying to perceive within our current situation in the metacrisis. The systems I mentioned at the start (AI slop, business-as-usual, capitalism) are so complex and interconnected that they defy comprehension through conventional means. So here's a question: could critical design help us navigate the massive gap between our collective cognition capabilities and these systems (if you haven't read my previous essay on the infrastructure of meaninglessness, you should!)? In order to answer this question, we have to understand that the infrastructure itself is part of a larger reality, something so massively distributed across time and space that our current tools are failing to help us grasp it.

Think about it. Information nowadays is mediated through text, audio, video, cut in bigger and smaller chunks, it is printed, it is sometimes open access and sometimes between walled gardens, printed and digital. It is then regurgitated by algorithms that provide statistical probabilities, and tell us what their creators think we like to hear. Then that information feeds back into the collective (mostly digital) information infrastructure, changed, distorted and full of hallucinations. This is a total breakdown.

This breakdown is not a recent development because what we're experiencing is not necessarily evidence of further corruption (it is), but rather a revelation (exposure to it). The systems meant to mediate our understanding of reality have always been extractive, manipulative, and oriented toward the production of subjects amenable to control. The difference now is that the mechanisms have become so totalizing that the illusion of neutrality has finally collapsed under its own algorithmic bias.

The present feels simultaneously frozen and accelerating, a condition Mark Fisher connects to "the slow cancellation of the future" (a term borrowed from Franco 'Bifo' Berardi). The future Fisher mourned as cancelled has given way to something more disturbing: a present in which the information infrastructure itself is actively weaponized, and our capacity to distinguish signal from noise is being systematically dismantled. During this moment that feels like an accelleration of systematic dismantlement, Franco Berardi argues that panic (or as I call it in the title: dread) has become the defining emotional state (affect) of our time. The core characteristic of this panic is information overload: we receive information faster than our brains can process it. When data flows at speeds that exceed our cognitive capacity, we lose the ability to think clearly about what we're experiencing (drawing from "What is philosophy?" of Deleuze & Guattari).

The panic exists alongside depression, both of them working as twin responses to this information overload and perceived powerlessness that keep us paralyzed and stuck. People oscillate between frantic activity (panic) and paralyzing withdrawal (depression), with neither state allowing for sustained, careful thinking required to address complex problems. On the other hand, the proper response to panic, as Berardi suggests, is to pause and refrain from action. Take a breath and slow down. On the contrary, panicked systems do the opposite: they accelerate, which is a reaction that creates a vicious feedback loop where speed produces panic, which produces more erratic activity, which increases speed further...

Panic stems from our interfacing with hyperobjects that are now confronting us directly rather than remaining abstract or distant. Timothy Morton coined and developed the concept of hyperobjects, defining them as "massively consequential realities that occupy vast expanses of time and space, confirmed by scientific understanding, while remaining so complex that they are always also stretching the limits of scientific explanation". Social media tend to exploit these realities for engagement and at the same time bad-faith actors manipulate their influential positions through distorting scientific findings and the messaging of their opposing positions for political gain. Political conflict now centers on identity rather than economic redistribution, amplified by algorithmic manipulation that weaponizes our information infrastructure against learning and comprehending itself.

This sort of collapse-prone state of the world requires us to grapple with new literacies:

- hyperobject literacy to engage massively complex realities without nihilism, panic, or depression

- platform literacy to understand digital manipulation, the politics of tech, power, and privilege

- systems literacy to trace connections between smaller systems and planetary processes, and how they affect each other

These new literacies cannot be taught solely through traditional means; they must be incorporated in behaviors that represent different ways of engaging with reality. They require a strong link between human cognitive capacities and hyperobject complexity without reducing that complexity to comfortable falsehoods, building subjectivity appropriate to our current situation, while at the same time avoiding cognitive overload and analysis paralysis.

This is a liminal moment as we stand between the collapse of 20th-century sensemaking institutions (the media systems, academic disciplines, and democratic norms that once provided epistemic orientation) and an unknown configuration that has not yet crystallized. In this threshold, critical design emerges as a necessary practice for navigating a crisis-ridden information infrastructure (check a really good podcast episode with Nate Hagens and Daniel Schmachtenberger on sensemaking).

Can critical design function more than just commentary? Can it serve as a means of rebuilding the conditions that enable meaningful learning, critical thinking, and collective action in an environment designed to prevent all three?

Critical design as cartography

Critical design then must operate within this terrain of panic, depression, weaponized information, and incomprehensible hyperobjects. It cannot generate culture in the sense that tech platforms generate products and services. Culture emerges from friction between existing power structures and practices that resist them. So critical design provides cultural cartography: mapping the terrain of our current regime while sketching the new pathways where alternative (and preferable) futures might become possible.

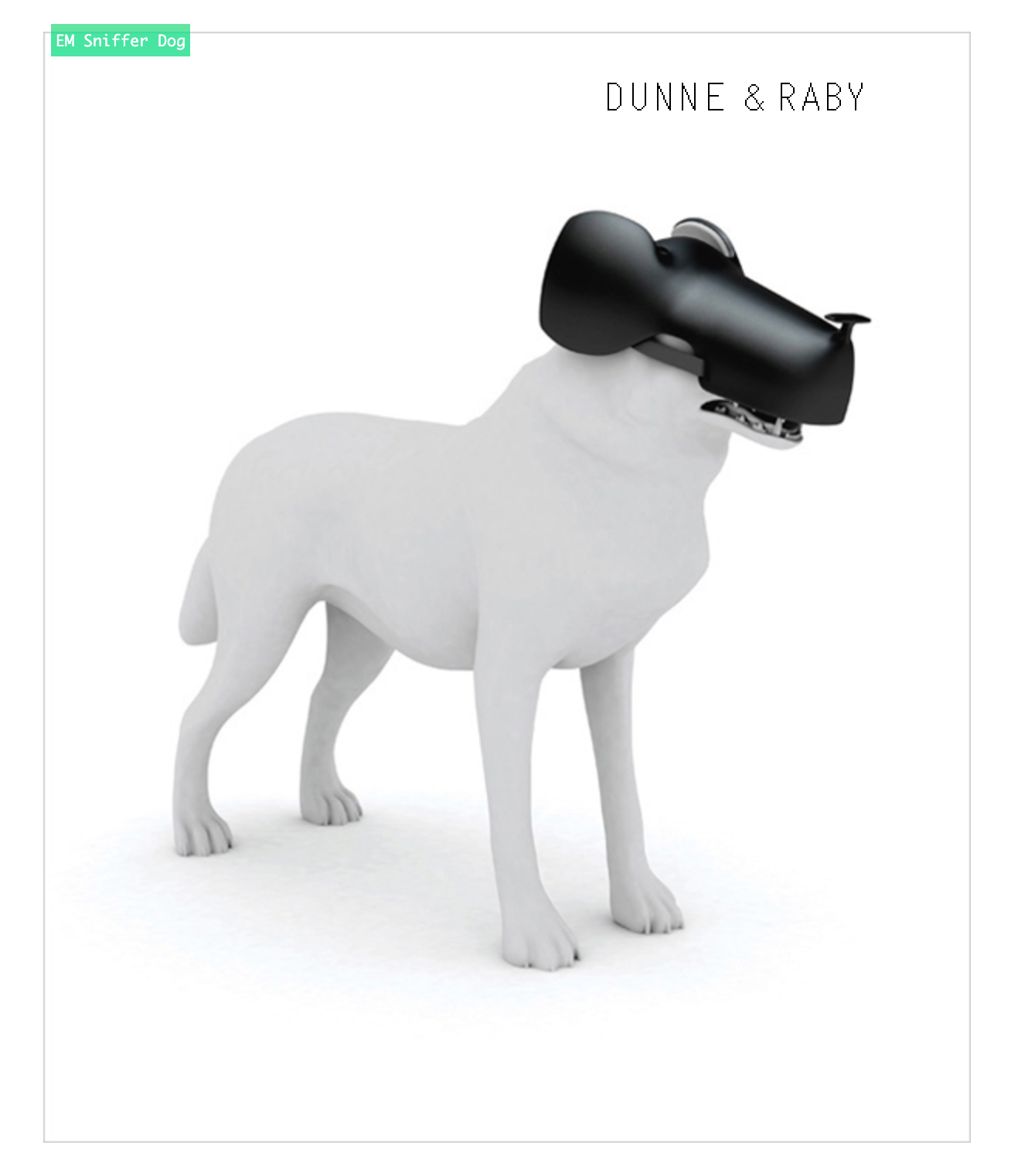

This sort of work (anthropological in its nature) unearths the beliefs, rituals, and power relations embedded in what we often tend to perceive as neutral objects and systems. When Dunne and Raby created speculative designs around surveillance and biotechnology, they made visible the ideological assumptions that naturalize certain technological trajectories (while foreclosing others). The hypothesis was very clear in that sense: every design choice encodes social relations. If we take the example of a smartphone interface that maximizes engagement, it implements a theory of human attention as an extractable and exploitable resource. Same thing with personal data and social media. The interface is a concretized political economy.

Critical design requires systems thinking because in order to critique a smartphone we need to trace its full lifecycle effects: lithium extraction, data center waste, dopamine manipulation, cycles of planned obsolescence, traumatized content moderators, addicted teens (and the list can go on in very complex paths). The smartphone in your hand links to climate change (through resource extraction and energy consumption), to geopolitical conflict (through supply chains dependent on conflict minerals and contested locations), to mental health crises (through designed addiction), to labor exploitation (at every point of production and maintenance), to democratic degradation (through algorithmic push of information and misinformation).

Kenya Hara's concept of "exformation" becomes something relevant the ponder upon here: where information adds knowledge, exformation creates space for new understanding by removing or questioning existing assumptions. Hara describes exformation as "the art of making things unknown again". This relates to Berardi's suggestion on how to cope with information overload. In an information environment saturated with data, propaganda, and noise, the capacity to unlearn becomes as important as the capacity to learn (even more important possibly). Exformation then becomes a tool of critical design when it defamiliarizes taken-for-granted technologies, making visible the choices that have been naturalized as an inevitability.

Of course, critical design cannot be an all-fitting mechanism, and currently, we can say that it is mostly confined in its institutional context. Gallery exhibitions and academic publications reach narrow audiences, which of course, are already sympathetic to critique. This is a problem by itself since critical design should break and create discourse more openly. The challenge becomes for critical design to achieve cultural relevance beyond designated spaces. The answer may lie in prefigurative prototyping: creating working systems that people can interface with, inhabit, and learn from.

If we stay with the example of a smartphone, we could think of FairPhone as a light example of prefigurative critical design. Fairphone attempts to create a modular smartphone with transparent supply chains and right-to-repair design. The project faces massive structural constraints from component availability (and ethical ways of obtaining it), economies of scale, and competition from extraction-based manufacturers. By conventional metrics, FairPhone is a project bound to fail. Yet its existence alters discourse about what actually constitutes a smartphone. It makes visible the specific mechanisms by which the industry depends on planned obsolescence, conflict minerals, and labor exploitation.

The concept aligns with Clifford Geertz's distinction between thin and thick description. Thin description tells us someone opened their phone 147 times yesterday. Thick description reveals what those interactions meant: anxiety bacause of precarious gig work, compulsive doomscrolling, erosion of unmediated time. FairPhone provides thick description as it demonstrates that current smartphone design embeds specific social relations that could be otherwise. In the end, the fact that alternatives face structural constraints becomes in itself a revelation about how power manifests through technological infrastructure and how it is interlinked with the tech industry.

Can critical design help shape culture or does it remain trapped in galleries and publications while planetary systems collapse and fascism advances? I think that this depends on whether critical design can move beyond its institutional bounds into direct engagement with the infrastructures that structure daily life. This means designing systems people actually use, or accepting the constraints and compromises that come with operating at scale while maintaining critical integrity. Building alternatives requires that they work well enough to compete with extractive systems, even when structural conditions make such competition nearly impossible.

Alas, critical design cannot solve the metacrisis by itself. It can, however, contribute specific practices:

- systemic analysis that traces connections between individual objects and planetary catastrophe

- exformation that clears space for new understanding by questioning naturalized assumptions

- prefigurative prototyping that builds working alternatives despite structural constraints

- temporal interventions that create spaces for slow thought in an accelerated information environment

- interfaces that mediate between human capacities and hyperobject complexity.

The liminal moment we inhabit is a threshold, genuinely undetermined. Critical design can help map and build a path through patient, material work: bringing together the tools, systems, and infrastructures that enable human thriving under conditions designed to prevent it. This is meaningful work in an age of panic. This is the slow, difficult project of rebuilding reality from the ruins of our information infrastructure.

Explore more

- Eeva Berglund - Design anthropology – from an environmental p.o.v.

- The Consilience Project - We don't make propaganda, they do - Education, Propaganda, and How to Tell the Difference

- Critical Playground - Speculative Cartographies - Mapping Futures with Communities

- Andreiw Budiman - “Design Pedaggedon: Utopian Daydreams in Today's Dystopia”

- Guilherme Fians - Prefigurative politics