Antinomies of design

Let's theorize design responses towards emerging and interconnected crises in 2026.

2026 started off already with unprecedented events (typical characteristic of the polycrisis) but we will not be talking about these events. However, on a similar note, since it's a new year and people get to turn hopeful of reflective, I was taking a look at Sitra's megatrends for 2026 and the topics they explore tie well with unprecedented events. Sitra identifies five megatrends converging simultaneously: democracy struggling under populist pressure, economic uncertainty colliding with green transition demands, AI transformation reshaping knowledge institutions, demographic shifts toward an aging-diverse society, and environmental crisis accelerating despite political resistance (Sitra is the Finnish Innovation Fund, FKA Helsinki Design Lab).

In extension, in broad strokes during 2026, design discourse will likely respond with familiar rituals of conferences celebrating "human-centered" approaches and teams rebranding around "responsible AI", performing concern and care while leaving underlying relations untouched. This sort of theater of professional malpractice matters because it maintains the illusion that design operates as neutral technical practice rather than a political economy where every interface, workflow, and solution implements governance, encodes labor relations, and determines who captures value and who bears the cost.

Fredric Jameson observed that under late capitalism, it became easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. Materially, this condition structures design practice in 2026 because (I would hazard a guess that many designers, especially if they have been working with systems) likely understand that current trajectories of business-as-usual lead toward an unsustainable world or worse, collapse. They likely recognize that growth and capitalism produce the crises they claim to solve, and the alternatives appear naive, impractical, and doomed to fail (any effort challenging extractive capitalism faces systematic disadvantage towards success).

This worldview (that Jameson articulated), which Mark Fisher would call capitalist realism, operates through absorbed assumptions about what counts as practical and realistic for our current predicament. A startup pursuing investor funding, scaling operations, and maximizing billable hours appears professional. A startup rejecting growth orientation while practicing alternative forms of governance (like equitable ownership among the workers), and prioritizing sustenance over expansion, appears idealistic. Certain organizational forms look credible while others look amateurish, regardless of their actual viability (politics as aesthetics).

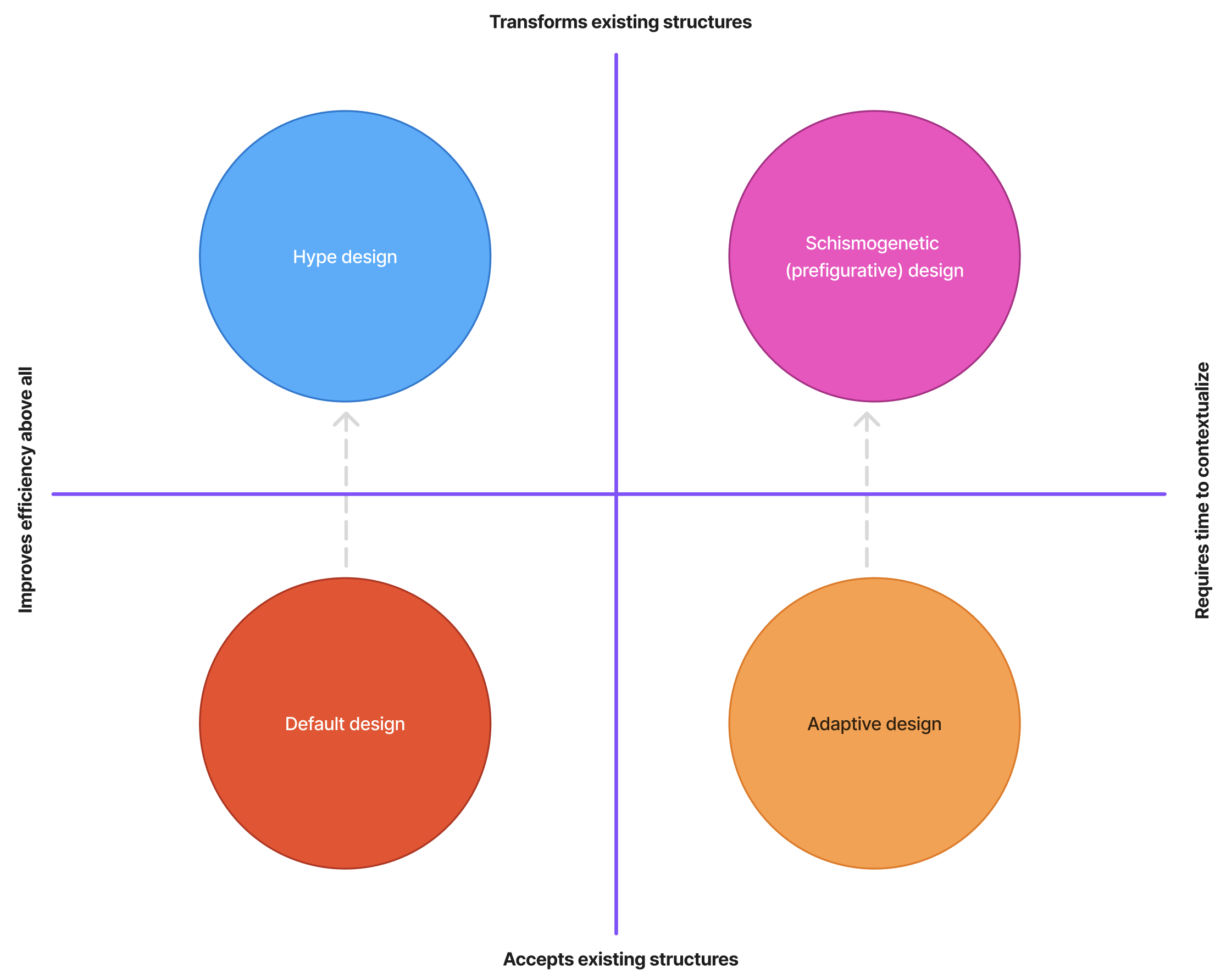

There are two antinomies that structure design work today:

- The first antinomy involves AI promising to 'eliminate repetitive labor' and 'enable strategic focus', yet actually intensifies extraction while compressing timelines and degrading working conditions. This contrasts with the slow nature of design, which requires time to understand, contextualize, and question before it acts.

- The second involves business-as-usual, where teams can accept growth orientation and extractive logic. This is versus a transformation that is needed in order to build alternative structures and address the polycrisis, which inevitably faces systematic disadvantage within markets structured purely around extraction.

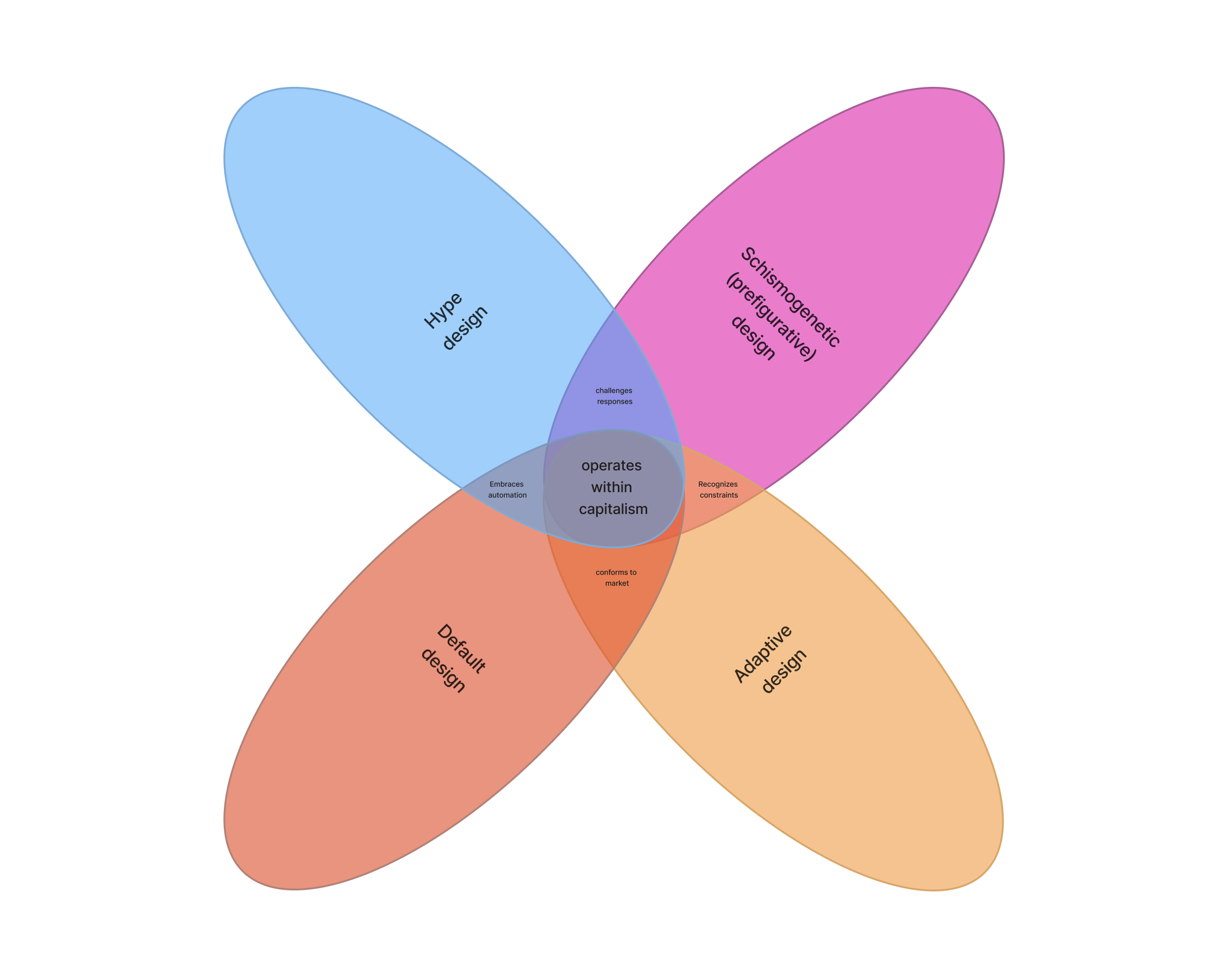

From these antinomies, I would like to hypothesize four design ontologies that emerge as responses to these conditions of our current predicament. Each represents a structural position within capitalist relations (not necessarily individual choices). Exploring these ontologies may help us grasp how something that appears as professional diversity (different team approaches, varied service offerings, aesthetic preferences) actually traces the limited options available when practice operates within foreclosed horizons.

Design ontology #1: Default design or naturalizing extraction

Default design operates while treating existing assumptions as de facto, and by doing so, it is helping businesses (that pursue investor funding, measure success through revenue growth, scale operations by hiring cheaper labor) to maximize efficiency through workflow optimization. This approach treats current climate breakdown projections and extractive practices as background conditions rather than failures requiring structural intervention that design may have responsibility over.

The naturalization of the status quo get obfuscated through crude language, where businesses and subsequently design teams discuss, for example, "market forces" determining wages rather than political choices about labor compensation. They describe "competitive pressure" requiring efficiency gains rather than growth imperatives serving particular class interests. They cite "investor expectations" demanding rapid turnaround rather than timeline compression, serving capital accumulation. In the magical world of business-as-usual, nobody decides about these things; they simply are how markets work, and this passivity in the language simply erases agency and the fact that they are all choices we make every day.

Crisis appears as a constraint for default design, something that requires mitigation. Whether it is democracy under pressure, economic uncertainty, AI transformation, demographics, or environmental breakdown, they are crises translated into a market opportunity that serves business needs rather than a civilizational emergency requiring structural responses. Any sustainability mention or action within default design represents weak sustainability: efficiency improvements within extractive structures.

The structures determine outcomes regardless of intentions. An investor-owned company must extract value to satisfy shareholder returns. This imperative operates whether individual designers identify as progressive or conservative, whether they personally support sustainability or dismiss it. The organizational form implements a strong worldview that individual ethics cannot override.

Design ontology #2: Hype design or acceleration as a solution

Hype design presents an acceleration of dominant logics, and every problem becomes an opportunity for AI deployment. In a wa,y hype design is an extension of default design. Every workflow requires optimization, and every decision needs algorithmic support. This ontology emerges from technological solutionism but also from competitive pressure. Companies adopt AI tools because competitors do it. The technology gets deployed simply because market position requires demonstration of some sort of illusion of innovation, not because it evidently solves specific problems.

The acceleration produces reflexive impotence (as theorized by Mark Fisher once again), where we know things are bad but cannot imagine acting effectively to change them, leading to accelerating the polycrisis as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Many designers understand that AI still serves extractive purposes, concentrates power and knowledge in platform monopolies, and intensifies surveillance capitalism, yet the solution offered involves more AI.

Crisis gets processed as a technical requirement. Democracy struggling? Deploy "civic tech platforms". Economic uncertainty? "Optimize resource allocation". Knowledge institutions failing? "Embrace AI". Aging population? "Personalization algorithms". Environmental breakdown? "Climate tech". Hype design claims to embrace the future while reproducing the present: workflow optimization and algorithmic management extend existing logics of control and extraction into new domains.

Design ontology #3: Adaptive design or survival without transformation

Adaptive design is simply design in survival mode. As the name suggests, this is not necessarity an extention of default design, but it's a rational response from designers in order to 'keep the job', till conditions become better. Designers accept structural constraints while seeking marginal improvements within their teams to meet performance review "quotas". This is a rational response to precarious conditions: budgets become tight, companies demanding more for less, competition is intensifying through AI-accelerated production timelines.

Adaptation reproduces precarity because designers survive by becoming more efficient within the same extractive logic, not by building alternatives. This ontology predominates for understandable reasons. Individual designers rejecting the dominant ways-of-working of default design operate at a total systematic disadvantage. Market pressures, investor expectations, and competitive dynamics push toward conformity.

Adaptation is pragmatic because it addresses immediate survival needs, yet pragmatism within destructive structures becomes a second-hand complicity. Survival through efficiency gains within systems producing these outcomes means accepting their continuation. Adaptive design treats structural constraints as facts requiring navigation rather than arrangements requiring challenge. The naturalization makes power invisible by treating its effects as variable conditions.

Design ontology #4: Schismogenetic design or prefiguring alternatives

We can call schismogenetic design anti-design because it aims to break free from the institutional constraints of the other three ontologies, and it emerges through active differentiation from a dominant practice. The term schismogenesis is borrowed from anthropologist Gregory Bateson, and it describes how interaction between groups can drive them toward increasingly divergent positions. Applied to design, it suggests that alternatives may emerge not through incremental improvement within existing structures but through building structures embodying different principles.

This critical approach rejects growth orientation through alignment towards sustenance: revenues cover costs and provide decent livelihoods without requiring expansion. It rejects extraction and hierarchy. The organizational structure itself becomes the designed object encoding different social relations. Rather than designing products for sustainable futures, we should design organizational forms that demonstrate alternative modes of being and doing businesses through continued viable existence. The practice collapses the distance between speculation and implementation that historically confined critical design to galleries and academia.

Yet such design faces structural constraints that puts it under systematic disadvantage from the get go. Conventional finance withholds capital access, and market pressures demand conformity. Legitimacy is measured on conventional metrics (revenue growth, staff expansion, media attention) incompatible with sustenance orientation. The permanent tension between extraction and cooperation cannot be resolved within growth-oriented structures.

What changes the equation involves collective infrastructure like knowledge commons, peer networks providing support, and federation. This mutualist infrastructure enables what might be called ecosystem emergence: multiple cooperatives succeeding through federation rather than individual organizations overcoming structural constraints through exceptional capability. This sort of design (or anti-design) must make alternatives visible not as speculative propositions but as material realities that people can inhabit, evaluate, and potentially join.

There is a political nature in professional choices

Default design and hype design embrace automation uncritically while adaptive design navigates automation pragmatically, adopting tools when competitive pressure demands it. Schismogenetic design challenges automation selectively, recognizing that efficiency at all costs serves particular interests rather than universal human flourishing. This is how these four ontologies respond to the first antinomy.

Default design and adaptive design accept existing structures while seeking success within them. Hype design amplifies existing structures through technological acceleration. Schismogenetic design attempts to build alternative structures despite systematic disadvantage within markets organized around extraction. This is how these four ontologies respond to the second antinomy.

The ontologies may be theorized as two axes. The vertical axis measures acceptance (accelleration) versus challenging (imagining alternatives) of existing structures. The horizontal axis measures efficiency (extractive) versus contextualizing (slow). Default design accepts structures and strives to improve operationaly within the current predicament. Hype design wants to challenge structures and responds through acceleration of new technologies towards a fuzzy future of artifacts with automation. Adaptive design accepts structures and responds through peer learning and mutual support. Schismogenetic design challenges structures and responds collectively through mutualist infrastructure that is prefigurative.

This distribution reveals the political nature of supposedly technical choices. Selecting tools, accepting work, structuring organizations, pricing services: each decision implements political choices whether designers recognize it or not. An investor-owned company maximizing profit may participate in labor exploitation because that's the way of things. A design studio as a cooperative practicing democratic governance may challenge hierarchical control. All of these can happen regardless of individual designer politics. The organizational form determines the outcomes that individual ethics cannot override.

This explains why transformation requires changing structures rather than changing minds. Many designers already understand that growth orientation produces crises, and extraction degrades ecosystems and wastes resources through duplication because of competition logic. The problem is not insufficient awareness but structural constraints making alternatives systematically disadvantaged as highlighted before. Constraints ensure that alternatives struggle regardless of how well people understand the problems within the context of business-as-usual.

What becomes possible

The current period creates specific conditions where structural transformation appears to be the hardest, but at the same time, it becomes feasible. Converging crises may be fertile ground for alternatives that capitalism cannot supply. And therefore, when we think back to those Sitra megatrends, we have our call to action outlined before us. Political instability requires demonstrating that democratic governance actually works against the backdrop of authoritarianism. Economic uncertainty strengthens the narratives of post-growth models. Technological transformation demands responsible implementation. Demographic change needs solidarity structures. Environmental breakdown requires regenerative practices.

Yet whether this moment enables transformation depends on whether practitioners, researchers, funders, and policymakers recognize that the organizational form constitutes one of design's primary prototypes towards addressing these crises. The most urgent design problem involves designing the structures within which good design work happens.

The organizational form of the future requires building mutualist infrastructure that enables ecosystem emergence rather than expects individual designers, or design studios, or teams to overcome structural constraints through excellence. Knowledge commons document what works and what fails, reducing barriers for subsequent attempts, and feeding that information openly. Peer networks provide support, preventing burnout when individuals struggle. Federation create collective strength through specialization and coordination rather than competition. Community land trusts remove property from speculative markets, providing stable, affordable space.

The infrastructure building represents design work operating at a different scale than the conventional practice. Rather than designing artifacts or services, it involves designing institutional arrangements enabling different economic relations. Rather than serving a company, it serves collective capacity to navigate contradictions that capitalism produces but cannot resolve. Rather than pursuing competitive advantage, it pursues collective viability through mutual support.

A prefigurative practice makes visible the fact that contradictions are structural, that their navigation requires collective infrastructure, and that alternatives to growth-first organizations can work when supported adequately. The design profession in 2026 confronts a political problem requiring structural transformation. The four ontologies we hypothesize represent limited responses to impossible conditions. What becomes possible depends on whether designers recognize that their professional choices implement a specific political economy, and whether they choose to build alternatives despite systematic disadvantage